Cosmetic and Textbook Reforms Will Not Solve Ethiopia’s Crisis

“As long as Europe and America control our money, they will control our economy. We need an African common currency backed by our resources and not by the dollar or the Euro.”

Paul Kagame, President of Rwanda

“Seek ye first the political kingdom,” Kwame Nkrumah, President of Ghana

Kwame Nkrumah once stated, “Seek ye first the political kingdom,” emphasizing that for African nations to thrive, they must first secure their sovereignty and establish robust political governance. In line with this, Paul Kagame, President of Rwanda, advocates for an African common currency supported by the continent’s resources rather than foreign currencies like the dollar or the Euro. These perspectives underscore a critical truth: effective governance and the development of strong national institutions are essential for sustainable progress.

Ethiopia, a trailblazer in African independence and unity, has tragically failed to achieve good governance and build the necessary institutions. Ethnic-elite capture, lack of peace and human security, and pervasive corruption have undermined state formation and equitable development. The country’s growth strategy, reliant on external aid and borrowing concepts from various sources, remains deeply flawed.

On July 29, 2024, Ethiopia celebrated debt relief granted by the IMF and World Bank under a Structural Adjustment Program (SAP). Historically, such programs have often been detrimental, as seen in 44 Sub-Saharan African countries and Argentina in the 1980s. While the IMF and World Bank’s role is clear—to implement policies established by their shareholders—the impact on Ethiopia’s development is questionable.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s administration has opted for the SAP without exploring alternative strategies. Choices such as scaling back extravagant projects, imposing higher taxes on luxury imports, and prioritizing agricultural modernization could have been considered. The lack of guarantee that funds will not be misused or diverted, and the potential for favoritism, casts further doubt on the efficacy of these measures.

The Ethiopian government’s policies have led to a domestic market in disarray. The devaluation of the Birr, exacerbated by a relaxed currency regime, has led to a significant drop in its value—30 percent against the US dollar. This free fall has intensified inflation and shortages of essentials, worsening the already fragile supply chain. Air travel costs have surged dramatically, and the government’s response has been punitive, shutting down businesses and exacerbating economic distress.

Ethiopia’s private sector, while holding significant potential, remains underdeveloped compared to other African nations. It comprises mainly small-scale, informal businesses and has struggled with industrialization and structural transformation. The failure of past industrialization efforts and the lack of sufficient jobs for the growing labor force highlight systemic issues within Ethiopia’s economic strategy.

The IMF and World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Program, embraced by Ethiopia without adequate preparation, has not stimulated the desired economic growth. Historical evidence suggests that devaluations have not effectively boosted export performance, with Ethiopia’s export earnings declining sharply from $8.5 billion in 2021 to $3.6 billion in 2023.

The sudden shift in Ethiopia’s exchange rate policy, driven by the desire to secure a $10.7 billion loan from the IMF and World Bank, has been criticized by economists and Diaspora groups. They warned of potential adverse consequences, which have now materialized in the form of economic instability and declining investments.

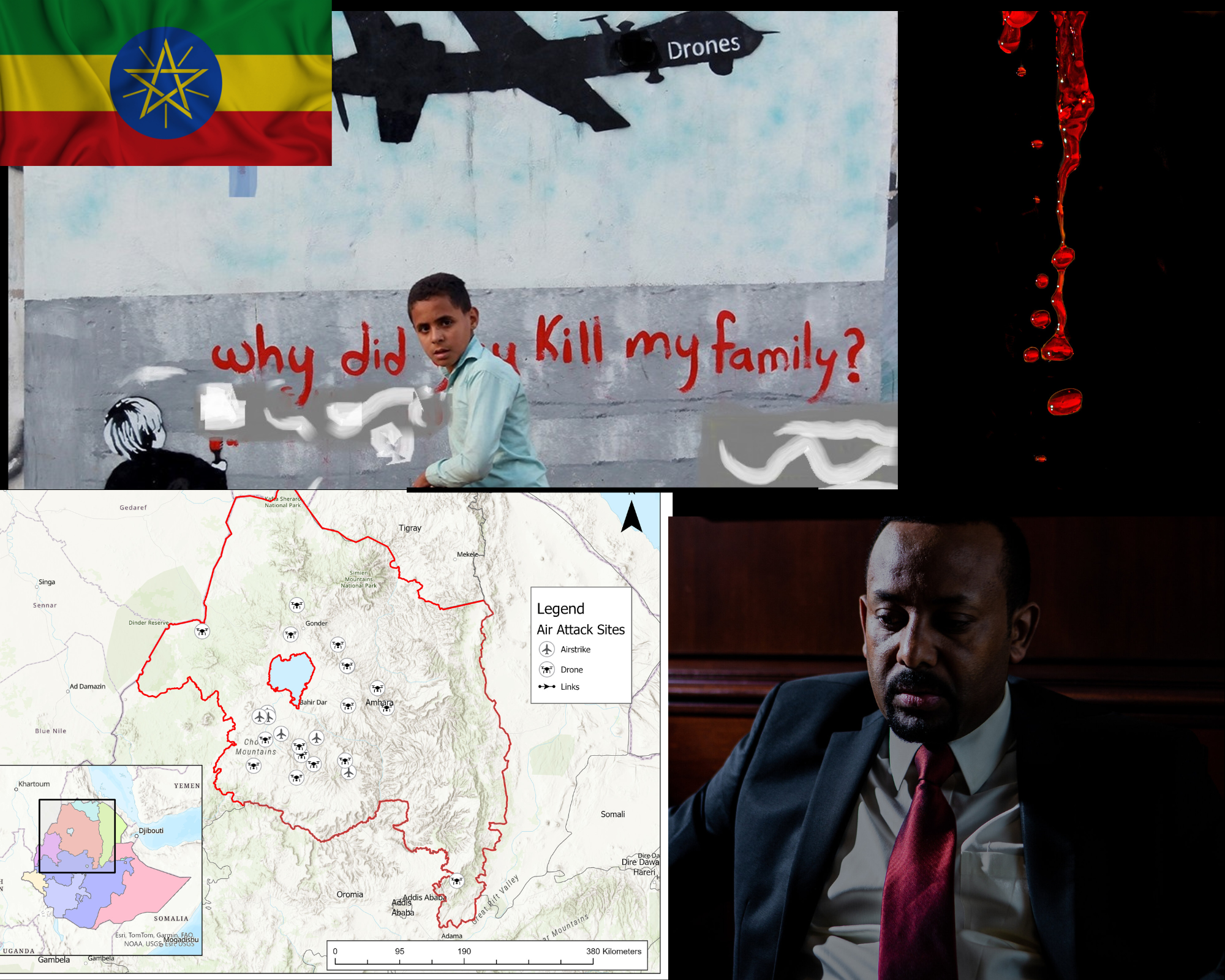

Ethiopia’s prolonged conflicts, including a brutal civil war and ongoing regional strife, have further compounded its economic woes. The lack of freedom and capital mobility, coupled with widespread lawlessness and broken trust in institutions, has stifled economic progress. The human and economic toll of these conflicts, including the loss of $49 billion in investments between 2020 and 2022, has been immense.

Despite the IMF and World Bank’s focus on ensuring debt repayment, they often overlook the broader context of Ethiopia’s economic challenges. The country’s external debt continues to rise, and its export sector remains stagnant, relying heavily on commodities with little diversification.

In summary, Ethiopia’s crisis cannot be resolved through superficial reforms or reliance on external aid alone. Genuine progress requires comprehensive, homegrown solutions and a commitment to addressing deep-rooted governance and economic issues.

Part 2 of 5 will explore and discuss the essence of “free trade” and neoliberal economics.

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in articles published by East African Review are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the perspectives of the editorial team or East African Review as an organization. The publication of any opinion piece does not imply endorsement by East African Review. We encourage our readers to critically assess the content and form their own opinions. We welcome your feedback and reflections; please share them in the comments below or email us at [email protected]