The underlying tension behind Ethiopia’s flawed federal system and its risks

For almost three decades Ethiopia’s federal structure – enshrined in the country’s 1994 constitution – has been defended by the ruling coalition, the Ethiopian Peoples Revolutionary Democratic Front.

It’s not surprising that the front has been the system’s prime advocate and defender. It oversaw the creation and implementation of the federal structure. Some of the country’s opposition elites also support the system. They believe it helps promote group rights, granting Ethiopians the right of self-administration.

But the federal structure has caused lots of problems for the country. This is primarily because it is constituted along ethnic lines. This is problematic because Ethiopia has a population of more than 108m and more than 90 ethnic groups. The biggest groups are the Amhara and Oromo. Together they comprise more than 65% of the population.

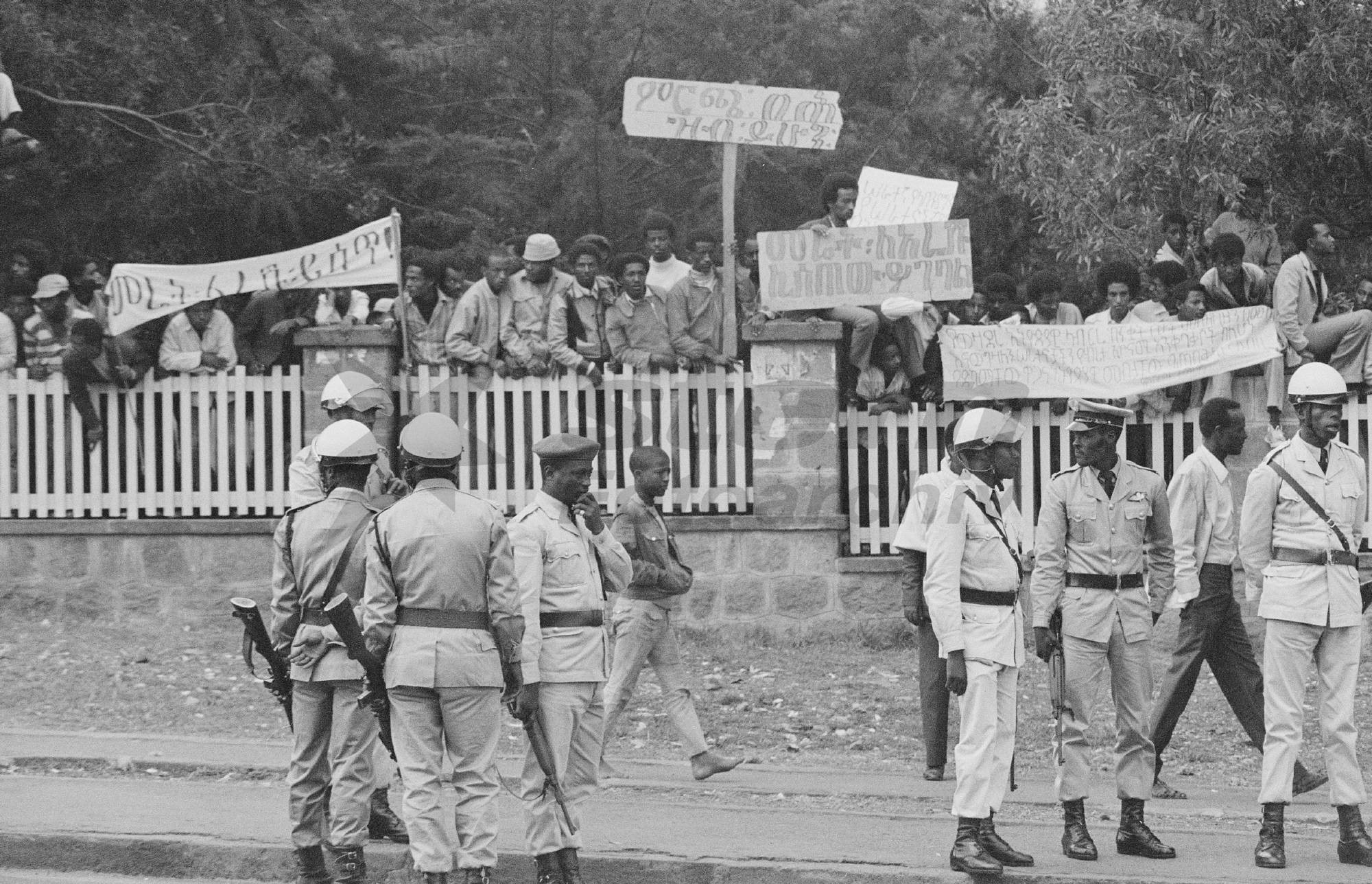

Before 1991, groups that took up arms against Ethiopia’s central government and its elites alleged rampant ethnic oppression and discrimination. But their claims were debunked for lack of concrete evidence. So when they had the fortune of leading a government and designing its structure they chose unique ethno-linguistic classifications for its creation.

Sadly, in a nation of more than 90 ethnic groups, the system created more animosity and competition for power and influence.

Now, Ethiopia’s government structure is a federation of nine regions.

Debates about the system have resurfaced since prime minister Abiy Ahmed took office in April last year. And the country’s parliament has set up commissions to look into some of the pressing issues facing the federal system. These include the need for national reconciliation and where domestic administrative borders should be drawn.

But the creation of regions as ethnic boxes resulted in fierce inter-ethnic competition. This has affected the safety of citizens as well as the freedom of movement.

Despite the willingness in debating it afresh, reaching a political consensus remains challenging.

There are also those who are deeply opposed to renegotiating the arrangement. Others believe the federal structure was imposed via a constitution that they weren’t consulted about in the first place.

The difficulty is that the federal design has created winners and losers. For instance, the Amhara elites believe that the design has negatively affected them because they were never consulted on its structure.

In my view, continued tension over the issue shows that the federal design never took into account the popular will when it was introduced. On top of this, it’s been used to protect the Ethiopian Peoples Revolutionary Democratic Front.

Ethiopia isn’t alone in facing the conundrum of federalism. Even where it’s considered a success, as in the US, the system faces constant challenge. But disagreements about federal arrangements rarely result in political turmoil that could potentially threaten the national union. This is because of the relative strength and independence of the judicial system and a functioning system of checks and balances.

But the challenges Ethiopia faces due to its federal arrangement are substantial. Nor does the country have strong enough institutions such as independent judiciary and agreed conflict resolution mechanisms.

Dysfunction in Ethiopia

Ethiopia’s federal system was flawed from the beginning because it didn’t foresee potential sources of conflict or that regional states would make claims against one another.

Trust among regional states was never high, and has deteriorated over the last three decades. On top of this, the federal government’s ability and readiness to mitigate or solve domestic conflict has been open to question.

Currently, there are regions and regional leadership that are having difficulty working together. The federal government at the centre is too weak to impose its will on the regional administrations. The result is that there aren’t common political and economic national standards across the country.

This has led to a dysfunctional system that’s been the major cause of internal displacements. Ethiopia now has more internally displaced people than any other country in the world.

But possibly the biggest problem is the effect that the federal system has had on minorities. Ethiopia has nine regional states and two cities that fall under the administrative mandate of the federal government. Each region is administered by an ethnic political party. Thus, territorial and demographically larger regions such as Amhara, Oromia, Tigray and the southern region are administered by parties that are members of the ruling coalition.

The other five regions are made up mostly of minorities and are economically undeveloped. They are administered by ethnic parties that aren’t part of the ruling coalition. Yet they’re known as “partners”. Their ceremonial allegiance guarantees a false promise of national consensus.

These regions are referred to as “developing”, giving the impression that they aren’t quite up to scratch. At the same time the ruling coalition constantly interfere in their local affairs. This is justified on the grounds that its part of a fight against corruption, correcting administrative incompetence or as punishment for failure to comply with federal government’s regulations.

As a result, Ethiopia’s federal design has relegated most minority regions that aren’t directly administered by the ruling coalition into second class regions. In turn this meant that the citizens are second class.

All of this shows that there isn’t a level playing field when it comes to the constitutional rights of all Ethiopians.

Recently, the ruling coalition announced the possibility of including partner parties from five regions into the coalition. But, as long as the federal design isn’t rectified, the reality won’t change.

There are dangerous indications that regions want to secede. For example, groups in the southern region – once considered as little Ethiopia – such as ethnic Sidamas and Wolaytas, are demanding statehood. Two recent demonstrations show that even those traditionally considered supporters of Ethiopian unity are preferring to establish their own ethnic regions.

The inter-ethnic violence across Sidama and Wolayta areas suggest that ensuring peace and stability across these areas is going to be challenging.

Solving the dilemma

Ahmed’s government faces a difficult dilemma trying to reconcile the voices in support of the country’s federal arrangement versus those who perceive it as a threat to their group, and the nation.

Crucially, pushing through the necessary debates and emerging with corrective measures that both empower all groups while also strengthening weakened national unity is tied to Ethiopia’s survival.

Finding common ground remains a matter of urgency.